Joan Ramon Resina was 16 in 1971 when his mother joined other parents to ask the school director for permission to hire a private tutor to teach students their native Catalan language.

Joan Ramon Resina was 16 in 1971 when his mother joined other parents to ask the school director for permission to hire a private tutor to teach students their native Catalan language.

If that sounds strange — Why would the director object? — consider that this was in Barcelona under the tyrannical Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, who had banned the language 30 years earlier in Catalonia, the northeastern corner of Spain that borders France and includes Barcelona. To many who live there, Catalonia is a nation within a nation and should be independent. But in the earliest years under Franco, those caught merely speaking, writing or studying Catalan were beaten or forced to drink almost a quart of castor oil. At best they were fined. At worst, shot. In 1974, Catalan activist Salvador Puig Antich became the world’s last person to be garrotted — executed in a strangulation machine.

So the parents’ request was radical, and they were denied. It meant that Resina didn’t learn to read and write in the language of his parents until he taught himself as an undergraduate at Brandeis University in Massachusetts.

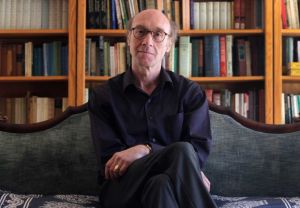

Today, he is not only a scholar of Catalan but is bringing its language, culture and literature to 21st century students while finishing a book on Josep Pla, one of the previous century’s most intrepid and prolific journalists that few have yet heard of. Resina’s efforts come as Spain has placed Catalonian President Artur Mas under criminal investigation for allowing a nonbinding independence vote to proceed in November. (Independence won, though less than half of the electorate voted.)

Combatting resistance

At Stanford University, Resina, 58, has transformed the department of Spanish and Portuguese into a “hotbed of Iberian studies,” he says, referring to the array of languages, literature and cultures — Catalan, Basque and Galician, as well as Spanish and Portuguese — that make up the Iberian Peninsula. The department was renamed Iberian and Latin American cultures in 2008.

Stanford has been open to the transformation, but Resina says it has taken decades for many universities to elevate minority literature from Spain.

Since moving to the United States permanently in the early 1980s, not long after Franco’s death in 1975, Resina says he’s lost jobs, been denied tenure and angered colleagues for emphasizing the importance of Catalonia, whose luminaries include the surrealists Salvador Dalí and Joan Miró, cellist Pau Casals, bandleader Xavier Cugat and, for Californians, the 18th century missionary Juníper Serra and explorer Gaspar de Portolà.

Since moving to the United States permanently in the early 1980s, not long after Franco’s death in 1975, Resina says he’s lost jobs, been denied tenure and angered colleagues for emphasizing the importance of Catalonia, whose luminaries include the surrealists Salvador Dalí and Joan Miró, cellist Pau Casals, bandleader Xavier Cugat and, for Californians, the 18th century missionary Juníper Serra and explorer Gaspar de Portolà.

Catalan is a Romance language that grew out of Latin and has elements of French and Spanish.

“Anti-Catalanism is the homespun equivalent of anti-Semitism,” Resina wrote in an essay on his professional life that is crammed with accounts of such affronts.

Even American scholars who criticized Franco “replicated the Francoist suppression of Catalan culture/literature in their programs,” he said in an interview. “This was true of virtually every U.S. university. … But at (UC) Berkeley it seemed even more shocking, given its liberal, antiestablishment reputation.”

Language’s revival

Resina had gone to UC Berkeley as a Fulbright scholar in 1982 to take a doctorate in comparative literature. He originally planned to study in England, but funding fell through after someone on the grant committee “asked me suspiciously if I was planning to write my dissertation in Catalan.”

“That possibility had not crossed my mind, since the state had done an excellent job at ensuring that I remain illiterate in my native language,” Resina wrote in his essay. But now he thought: “Why not?”

At Berkeley he urged the department of comparative literature to recognize Catalan literature. That worked, he said, but he was less successful as he moved on to teaching jobs around the country, where he said his efforts were often met with hostility from native Spaniards and from colleagues pushing for greater emphasis on Latin America.

He recounts that at Williams College in Massachusetts, someone sent him a news clip mocking people who studied Catalan. He said he turned down an appointment at Harvard after learning that a senior faculty member objected to his having published an article on Mercè Rodoreda, a Catalan novelist. As he prepared to leave his job at Stony Brook University on Long Island, he discovered that the Catalonian government had sent money to expand the teaching of Catalonian literature — three years earlier. No one had told him. And at Cornell, he said, colleagues boycotted lectures by Catalan speakers.

He recounts that at Williams College in Massachusetts, someone sent him a news clip mocking people who studied Catalan. He said he turned down an appointment at Harvard after learning that a senior faculty member objected to his having published an article on Mercè Rodoreda, a Catalan novelist. As he prepared to leave his job at Stony Brook University on Long Island, he discovered that the Catalonian government had sent money to expand the teaching of Catalonian literature — three years earlier. No one had told him. And at Cornell, he said, colleagues boycotted lectures by Catalan speakers.

Much has changed, and today the literature and language of Catalonia are offered at universities across the country. Even in Catalonia, revival of the native language is so thorough that parents complain schools don’t teach enough Spanish. But to the guy who grew up under the oppressive Franco, introducing the world to Catalonia’s literary legacy remains a mission.

Pingback: Let me say one thing. The quote of Pau Casals.